The Challenges posed by Population Aging

Author: MAPFRE Economics

Summary of the report’s conclusions:

MAPFRE Economics

Population aging

Madrid, Fundación MAPFRE, February 2019

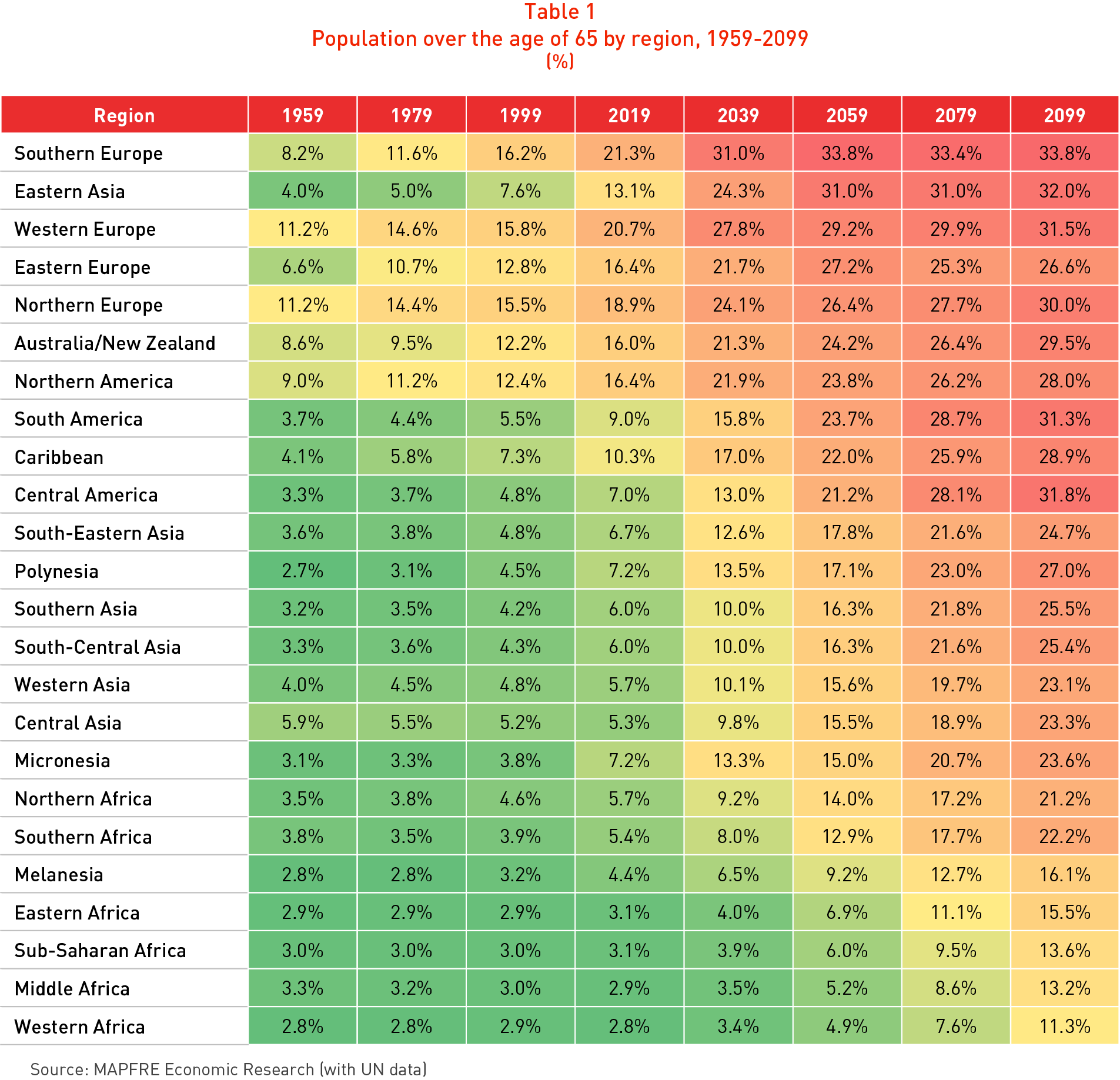

Population aging resulting from the combination of falling birth rates and a generalized increase in life expectancy constitutes one of the major challenges of our era. Table 1 shows the global change in the percentage of the population aged over 65 years, calculated on the basis of United Nations historical data and projections and broken down by geographical region.

It can be seen that in 1999 it was only in certain regions such as Europe, Australia & New Zealand and North America that more than 10% of the total population were aged over 65, and if the Far East and the Caribbean were excluded this ratio fell to under 5.5%. However, in the projections for twenty years from now (i.e. for 2039) the ratio is significantly higher than 20% for all developed economies, and approaches 30% by 2059, with even higher figures in Southern Europe and East Asia.

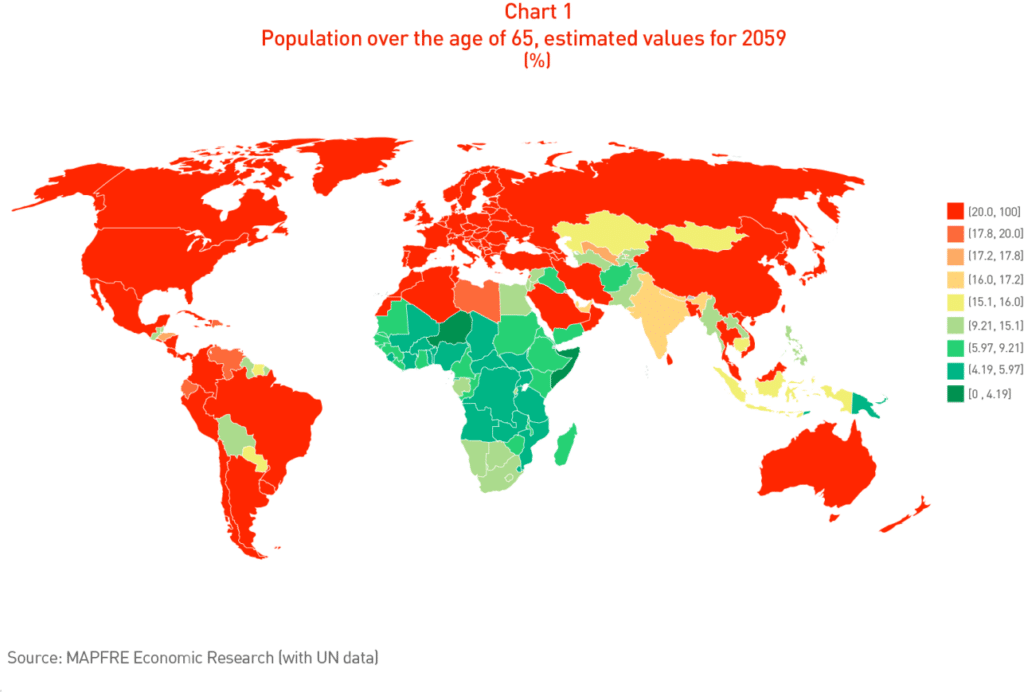

Chart 1 shows the worldwide situation in 2059, broken down by country.

Budgetary impact: expenditure on retirement pensions and healthcare

This process of demographic transition anticipates a progressive increase in the pressure placed on public expenditure as a result of the increase in pension and healthcare spending caused by the increased ratio of older people in the total population.

According to data provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), combined expenditure on pensions and healthcare represents between a third and a half of total direct government spending in OECD countries, so that the future increase of this expenditure anticipated by population aging will lead to significant pressure on their respective national budgets. In proportion to the inability to cover requirements, the increased budgetary pressures will affect coverage ratios for retirement pensions and public services related to healthcare, including the cost of long-term care.

Pension costs: two significant indicators

In the case of pensions, the elements of apportionment included in most current systems mean that the increased pressure on public accounts is to a great extent matched by the decreasing trend in the numbers in active employment as a ratio of the total population. The contributions paid by the former to support the retired population (via the mature dependency ratio) and the increase in life expectancy to the age of 65 years (the effective typical retirement age) are the principal factors here. The latter indicator is also particularly significant in terms of the basic elements relating to the capitalization of pension systems.

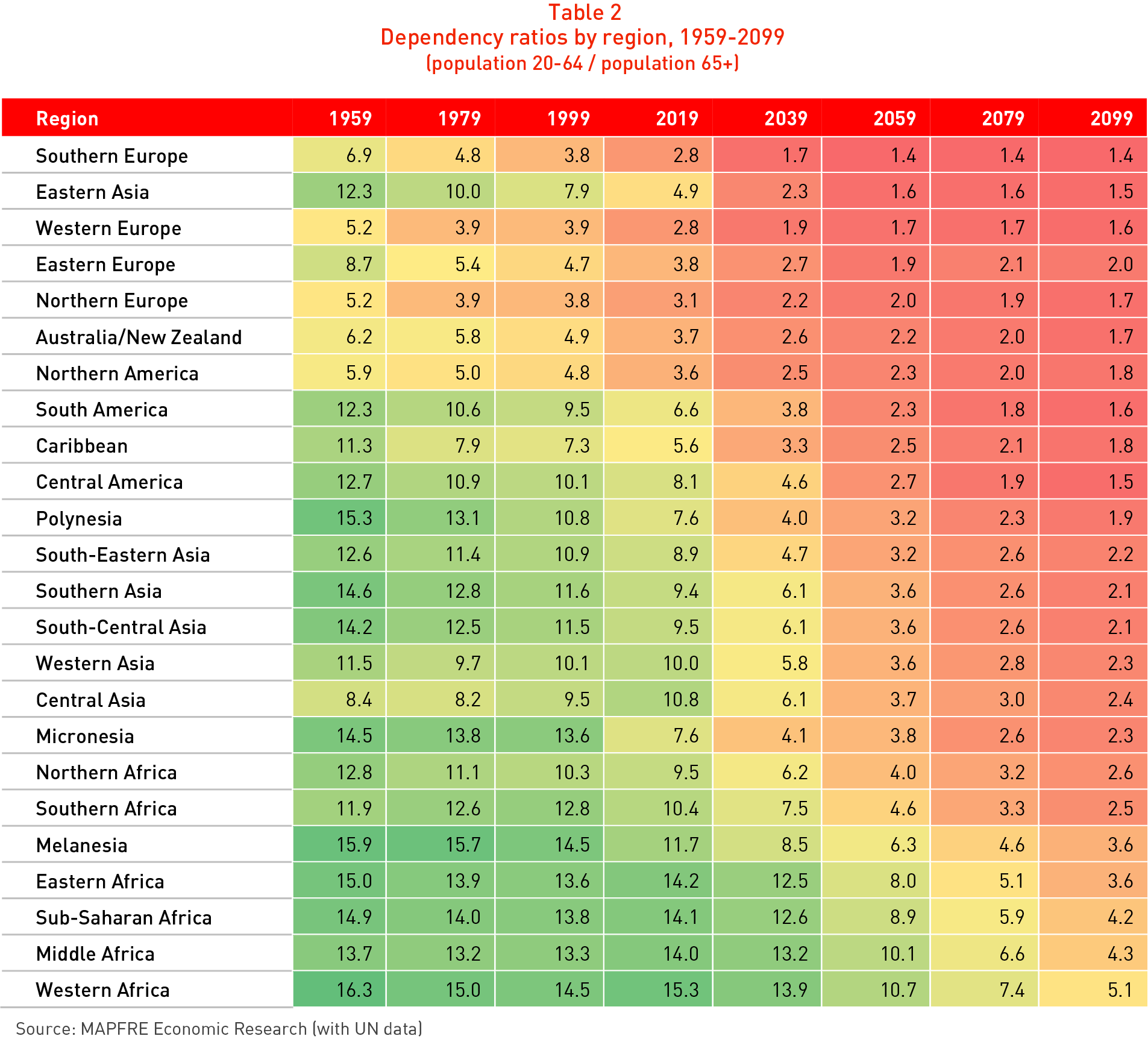

Table 2 shows the change in the dependence ratio, defined for the purpose of our analysis as the number of persons of working age for each retired person, taking into account a scenario in which the average age of entering the labor market is approximately 20 years and the effective retirement age is 65 years.

From the analysis of the ratios shown in Table 2 it can be seen that in Europe, Australia and North America the ratio currently (as in 2019) displays values of fewer than four persons of working age for each person who had reached the age of retirement. The figures for the Southern Europe and Western Europe regions are particularly revealing, each with current levels of 2.8 persons of working age per retired person, but which according to United Nations 20-year estimates are projected to fall to 1.7 and 1.9 respectively by 2039.

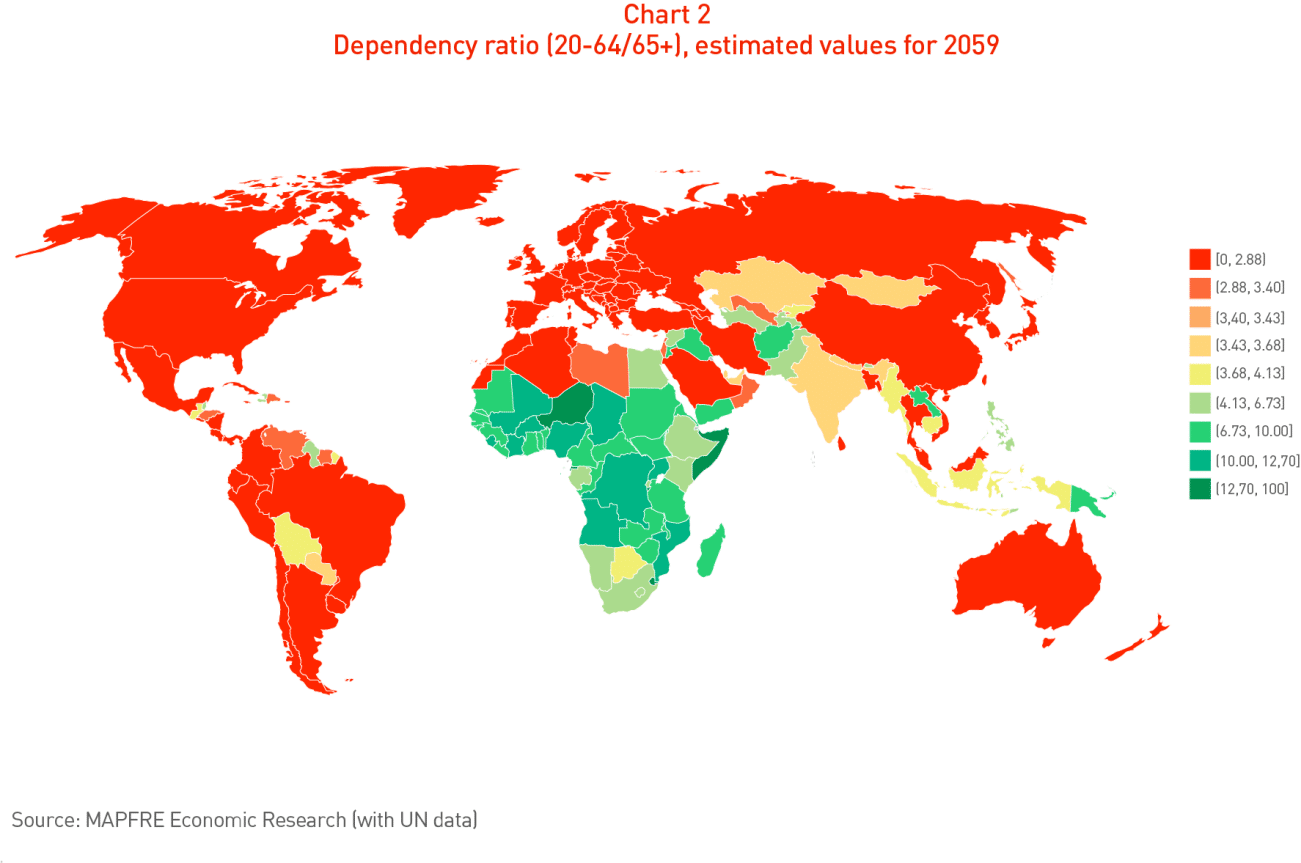

Chart 2 shows the worldwide situation in 2059, broken down by country.

The country-by-country analysis makes it clear that in the coming decades countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Spain, Hong Kong, Greece, Portugal, Poland, Singapore and Italy will reach dependence ratio values of under 1.5 persons of working age for every person who reaches the age of retirement. Only certain African countries, Iraq and Papua New Guinea display ratios approaching four or higher in projections for the end of the century. In summary, this information clearly confirms the process of a progressive reduction of the ratio of the working population to the retired population on a global level anticipated for the coming decades.

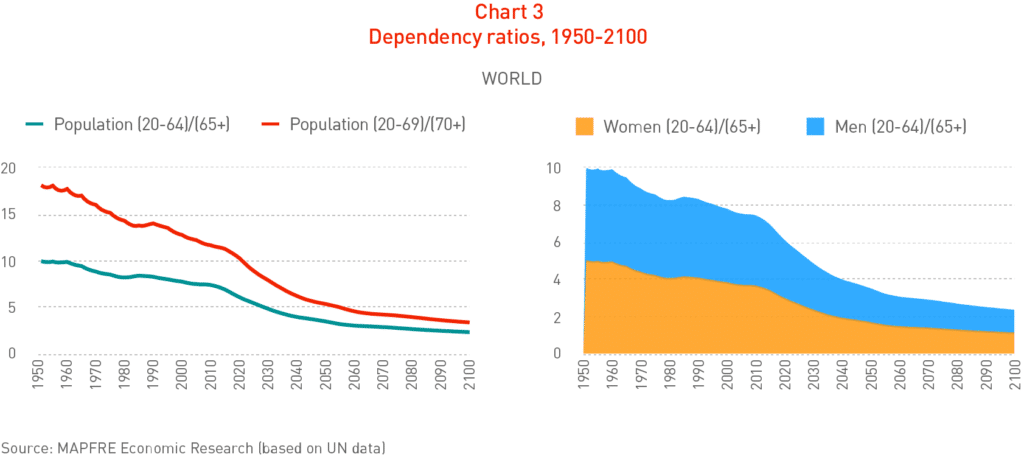

If we carry out a sensitivity analysis, prolonging the age of effective retirement to 70 years, it can be seen that the situation improves considerably, although the trend continues in the direction of a marked decline (see Chart 3).

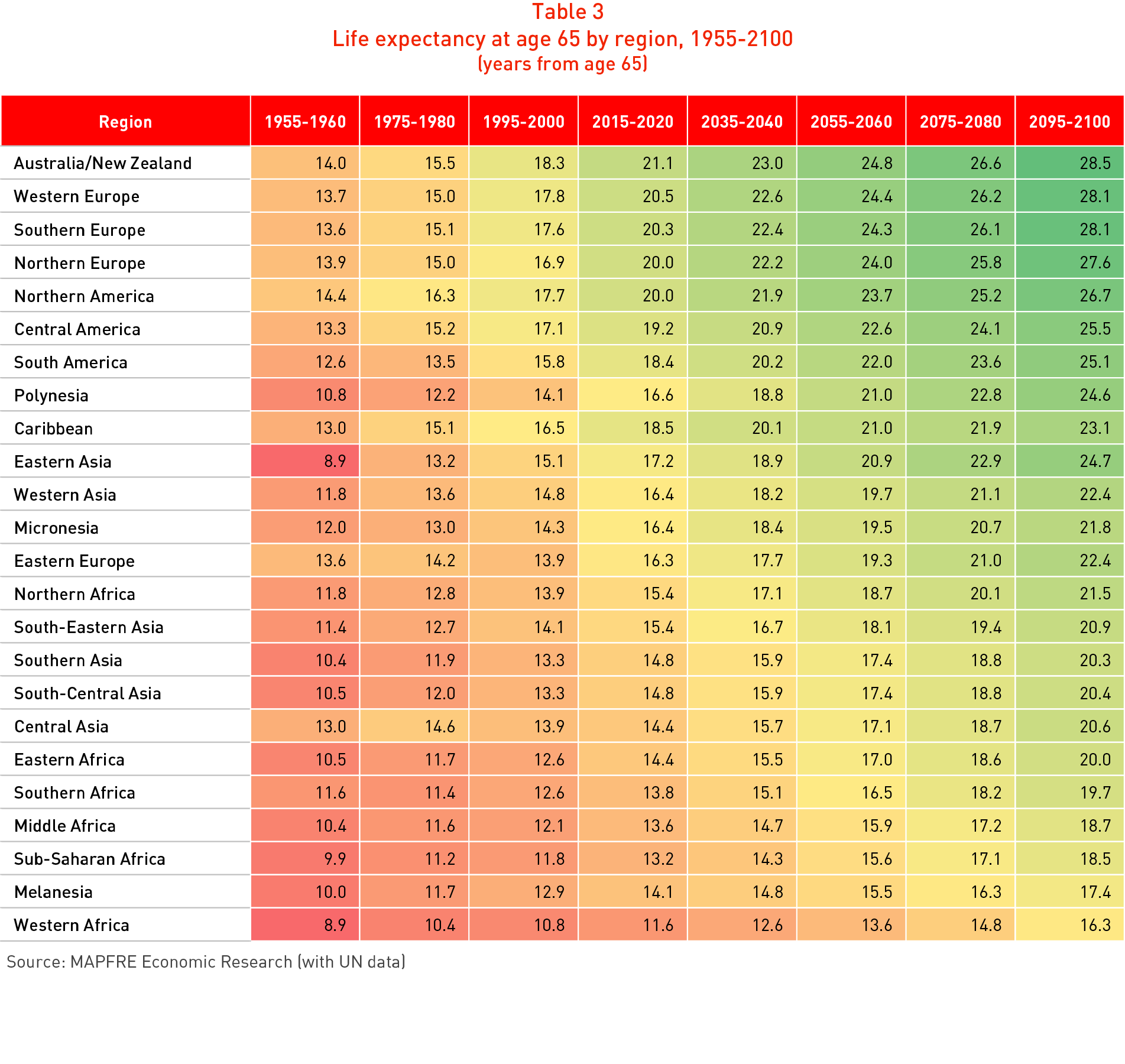

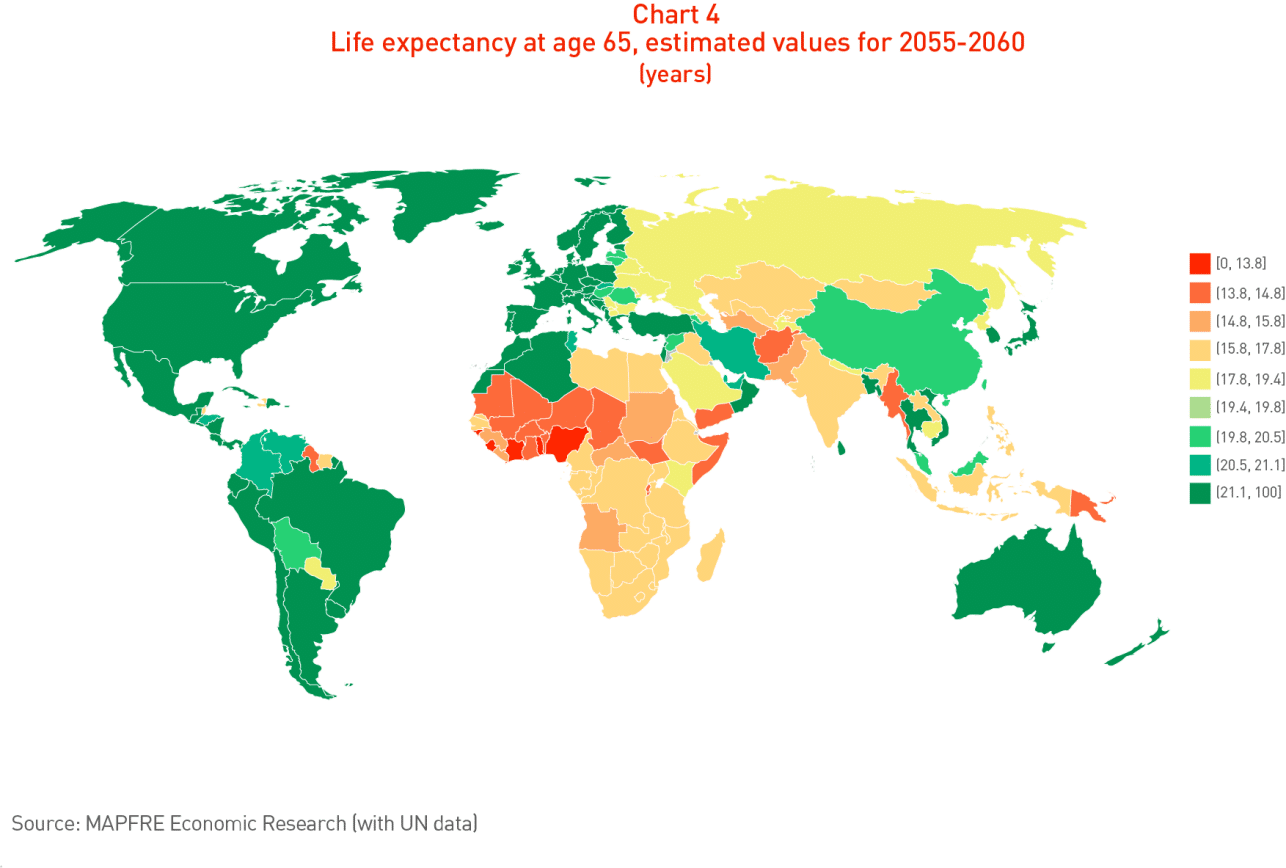

The second particularly significant indicator for pension systems is that of life expectancy at age 65, which represents the average length of time that retired people will receive their pensions. Table 3 shows the global change, calculated on the basis of United Nations historical data and projections and broken down by geographical region.

It can be seen that the Australia & New Zealand, Europe and North America regions currently have levels of life expectancy of 20 years or more at age 65. In projections for the 2055-2060 period, this will rise to over 23 years, while the projections for the end of the century attain 28 years in some areas of Australia & New Zealand, Western Europe and Southern Europe.

The country-by-country analysis that can be seen in Chart 4 makes it clear that in the coming decades countries such as Hong Kong, Macao, Japan, Martinique, Singapore, France, Guadeloupe, Spain, South Korea, Switzerland and Italy will attain levels of life expectancy at age 65 of 25 years or more by the 2055-2060 period and that this will approach 30 years by the end of the century, while the countries of sub-Saharan Africa will have the lowest levels of life expectancy.

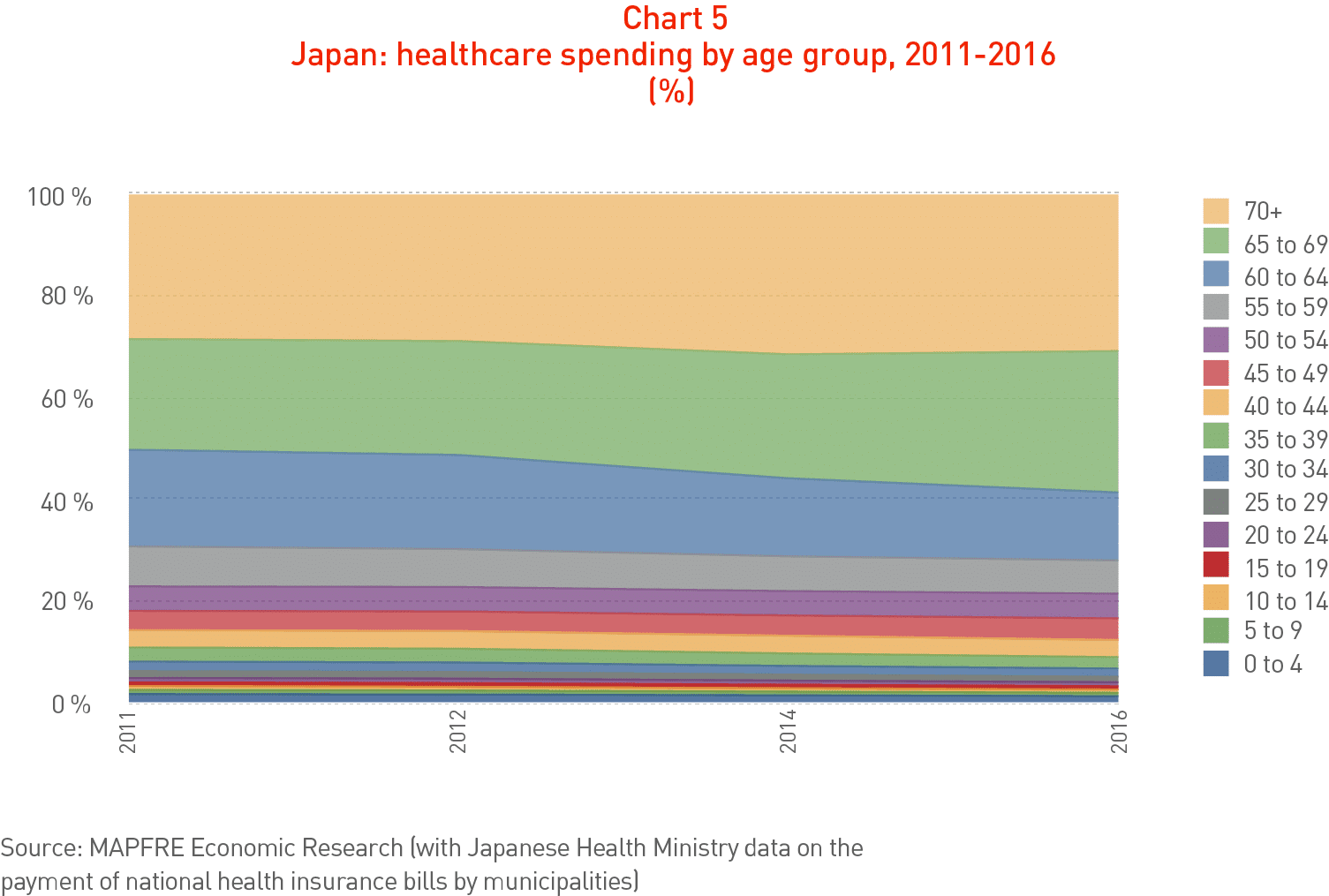

Healthcare expenditure: the Japanese experience

Since 2011, local authorities in Japan have been collecting data relating to the healthcare costs of the country’s national health system borne by municipal councils (ranging from large cities and towns to smaller local communities), broken down by age and types of illness. The analysis of the data available up to and including 2016 is shown in Chart 5 and reveals that persons over age 65 receive approximately 58.5% of total healthcare expenditure.

This means that the demographic transition represented by population aging will have a major impact on total healthcare costs as new cohorts of persons reach age 65.

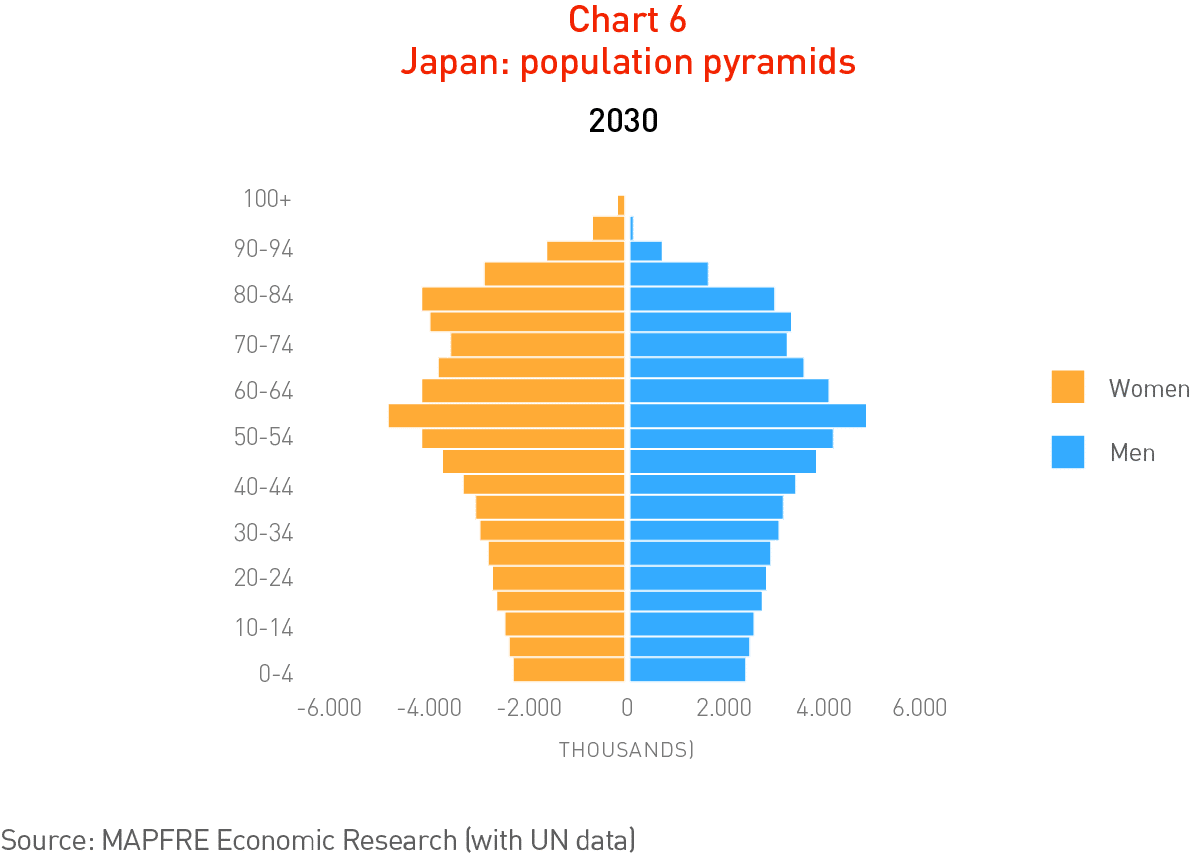

The Japanese population pyramid projected for 2030 (Chart 6), based on United Nations estimates, shows the incorporation of extensive cohorts of persons reaching age 65 from this year onward, which will substantially increase their healthcare costs. It can be assumed that this process will be reproduced sooner or later in most parts of the planet.

The importance of employment policies in the labor market

Longevity and public pension policies

Faced with the pressures of the demographic transition, the route that offers the greatest opportunities of bringing medium- and long-term sustainability and stability to pension systems is to attain a better balance between systemic pillars as a mechanism for redistributing the risks to which such systems are exposed. In the long run this will make it possible to better absorb the economic effects arising from their potential advent. From a methodological viewpoint, the analysis of various reforms introduced internationally in recent years shows that they tend to comply with the following principles:

a. Maintenance and reinforcement of a basic system of social protection (Pillar 0); i.e. a minimum non-contributory solidarity pension to support the strata of workers who were unable to complete their working life and therefore do not qualify for a contributory pension.

b. The creation of a first contributory pillar that combines intergenerational solidarity with the effort of individual saving, aligning benefits more closely with individual contributions.

c. The generation of incentives for companies to create and manage (directly or indirectly through professional fund managers) supplementary pension plans of the contributory variety (especially defined contributions) to complement Pillar 1 contributory pensions.

d. Incentives for medium and long-term voluntary individual saving which workers can channel through professional managers with financial products designed to generate an income during retirement, thus supplementing the pensions from Pillars 1 and 2.

Longevity and public healthcare policies

The traditional patterns of healthcare model (i.e., the Bismarck, Beveridge or free market systems) are currently becoming less clearly-defined, with a trend toward the extension of universal healthcare cover to all persons residing in each country either free of charge or with the sharing of costs, through the use of variants or combinations of the original models.

Independently of the specific healthcare model, the public sector thus plays a fundamental role in establishing the public policies required to implement the obligation of healthcare providers (both public and private) to provide adequate healthcare to the persons whose entitlement to such services has been recognized.

The way in which this cover is provided follows various patterns, with a variety in the types and forms of participation on the part of institutions and healthcare providers, in the financing of services and even in the scope of the cover provided. Whatever the case, the current generalized increase in the volumes of public debt and fiscal deficit in the majority of countries, aggravated by increases in pension costs, make it difficult to extend the budget for the public financing of universal healthcare cover and, as already mentioned above, the problem will only worsen in the future as a result of population aging.

A review of international experience based on a range of healthcare systems displaying a high level of effectiveness points to the existence of a range of public policies that can be highlighted as factors to be taken into consideration when confronting the challenge of demographic transition:

a. Savings plans to reduce healthcare costs: The linking of medium- and long-term savings to the provision of healthcare requirements has always been one of the aspects that has been considered as a key factor in improving public healthcare services. In this respect, the health system in Singapore has incorporated a citizens’ saving scheme with a view to providing for their future healthcare requirements (under a system known as “Medi-Save”). Through this mechanism, citizens can rely on funding that builds up while they are in good health so as to cover their future healthcare costs.

b. Incentives for taking out voluntary health insurance: These usually take the form of tax breaks for the contracting of individual or collective voluntary health insurance, with a view to relieving the burden on public healthcare systems. In certain countries (e.g. Australia), the incentive takes the form of penalization through income tax, with a progressive additional surcharge imposed on the rate paid to finance the public system if no private health insurance is taken out.

c. Insurance markets and price comparison websites: Various countries in which private health insurance policies play a significant role in the general healthcare system have introduced regulations to establish comparison websites so as to facilitate the comparison of prices and the cover provided. In the United States, for example, in addition to the provision of tax receivables, a digital market has been created for what are known as “Small Business Health Options Plans” (SHOPs), with a view to encouraging small and medium-sized companies to take out private health insurance for their employees. There are also digital platforms for taking out individual insurance policies managed by each state or, in their absence, at a federal level with standardized policies that are legally required to provide minimum healthcare cover (known as “exchanges”).

d. Consolidating the role of private insurance: The role played by insurance companies is to a great extent determined by the healthcare model of the territory in which they operate. They normally play a role that is complementary to that of the public sector. Consolidating the role of private insurance: The role played by insurance companies is to a great extent determined by the healthcare model of the territory in which they operate.

e. Correction of market failings: Finally, it should be noted that in those countries that operate a healthcare system based on a free-market or shared-cost pattern, there are public welfare programs for specific more vulnerable sectors of the population, including the elderly and those with low incomes, who otherwise would not have access to healthcare cover at a reasonable price. Taking into account the concentration of personal healthcare costs from age 65 onward and the trend toward an ever-increasing number of the persons who will form a part of these cohorts, public policies that introduce such corrective mechanisms into the operation of the free-market system are destined to acquire ever greater significance.

The study Population aging prepared by MAPFRE Economics develops further the topics dealt with in this article. This study is available via the following link: